KQED’s Otis Taylor: Centering Marginalized Voices Matters In Journalism

November 17, 2021

Acclaimed writer and editor Otis R. Taylor Jr. says that some of his most important work has been sitting and listening to the stories of the unhoused in the Bay Area – and that more journalists today need to take time to speak with, and focus on, the “historically marginalized and oppressed people” who are at the center of their news stories.

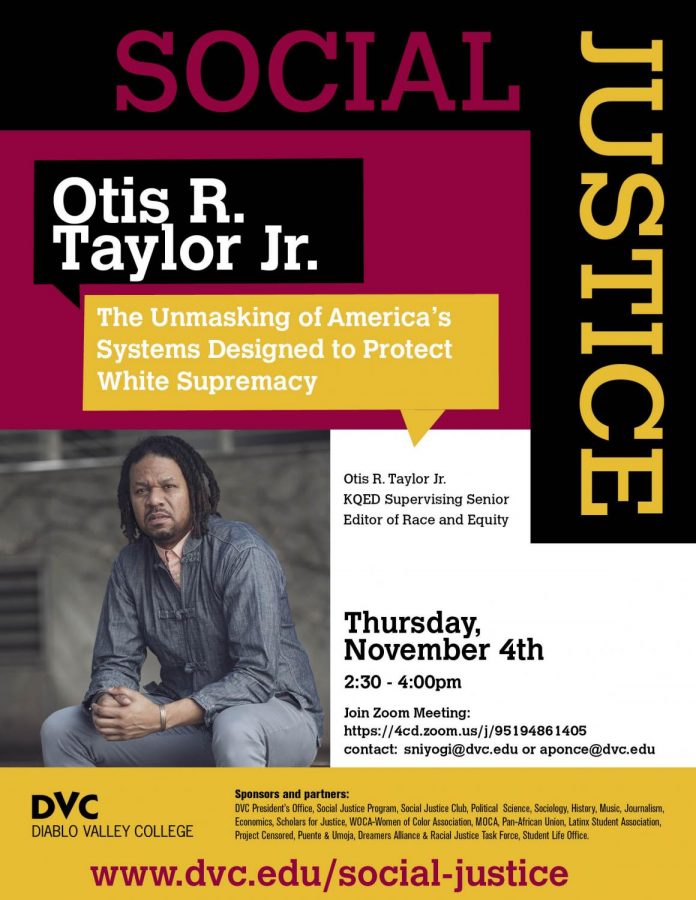

“The representation of non-white people in the media, since the profession’s inception, has been dictated by the white lens,” Taylor said.

Taylor – who worked previously as a columnist at the San Francisco Chronicle and a reporter at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and currently holds the title of Supervising Senior Editor of Race and Equity at KQED – spoke recently to Diablo Valley College students at a Social Justice Speaker Series event entitled, “The Unmasking of Systems Designed to Protect White Supremacy.” There, he discussed the ways the news media continue to uphold a legacy of white supremacy by featuring the voices and stories of those who already hold power in our society, and how we can change that.

Taylor’s position at KQED is unique. After George Floyd’s murder by police in 2020, the media outlet wanted to reframe the way it covered stories about diverse communities, so it hired Taylor to work with reporters and editors to bring a greater level of cultural competency to their work.

He said people often ask him why he “doesn’t write about something happy.” Taylor said he replies, “I’m not a clown, and I’ll be happy when structural systemic racism is understood as not simply a personal prejudice but rather a set of disadvantages that start with the average white child being born into families that have more wealth than your average child born into a family of color – and how that advantage extends into laws related to criminal justice, housing, voting, bank lending, and educational systems.”

The media itself plays a large part in furthering systemic racism, Taylor believes. “For far too long, the journalism profession has just allowed people with power to speak for those who don’t have any power, which doesn’t even make sense because people who don’t have power will tell you exactly what they need.”

Taylor said he thinks it’s up to journalists today to change this pattern.

“It’s incumbent on myself in this job, and the journalists I work with, to go and talk to the people who don’t have power, because for far too long this profession has allowed people with wealth and access to resources to dictate the narrative of people without.”

An example of this discrepancy took place after a violent attack against members of the Bay Area’s Asian American community. Taylor’s coworkers had planned to include quotes from the city council and local police, but he questioned why they had not gone specifically into Chinatown to gather interviews.

“I asked, ‘Are you going to talk to any Asian people, any people that live or work there?’” he said. “‘You’re doing a story about what the response is to a community impacted by senseless violence and you’re not talking to the community – how is that acceptable?’”

Taylor has always designed his social justice work “from the bottom up” and encourages others to do the same. “We have to do a better job,” he added. “We cannot call ourselves professionals if we are doing a half-assed job.”

According to Taylor, one problem is that many want to “blame people for their station without acknowledging the rules of this country that put people in that station.” He said he wanted to hear less from public officials who aren’t doing anything and center voices who have been historically repressed instead.

“Black Americans have lived under the shadow of institutionalized racism – the institution of slavery, followed by the institutional racism in regards to the Jim Crow laws, massacres, lynchings, sundown towns, redlining, the killing of people of color by police with impunity,” Taylor said.

“And by my paper napkin math, white people have had a 400-year head start on anyone else in this country.”

Taylor challenges those who are entering the journalism profession to consider two things:“Is the story you are being told true, and who benefits from the story being told?”

He concluded, “We have to hire more people who want to respond to injustice, and the way we respond to that is by telling stories about real people – telling real stories, and giving voice.”