Black History Mobile Museum Makes its Return to DVC

The Black History 101 Mobile Museum made its way back to the DVC campus on Tuesday, Feb. 15, as part of a two-day experience to engage students and honor Black History Month.

The mobile museum has visited over 500 institutions across 41 states as a “premiere traveling exhibit,” according to the museum’s website. Dr. Khalid El-Hakim, the CEO and founder, said he has spent the past 31 years traveling the country acquiring primary sources in hopes of telling the “story of the black experience in America.”

“I want students to be empowered, inquire about the material, and take responsibility for their learning,” said El-Hakim.

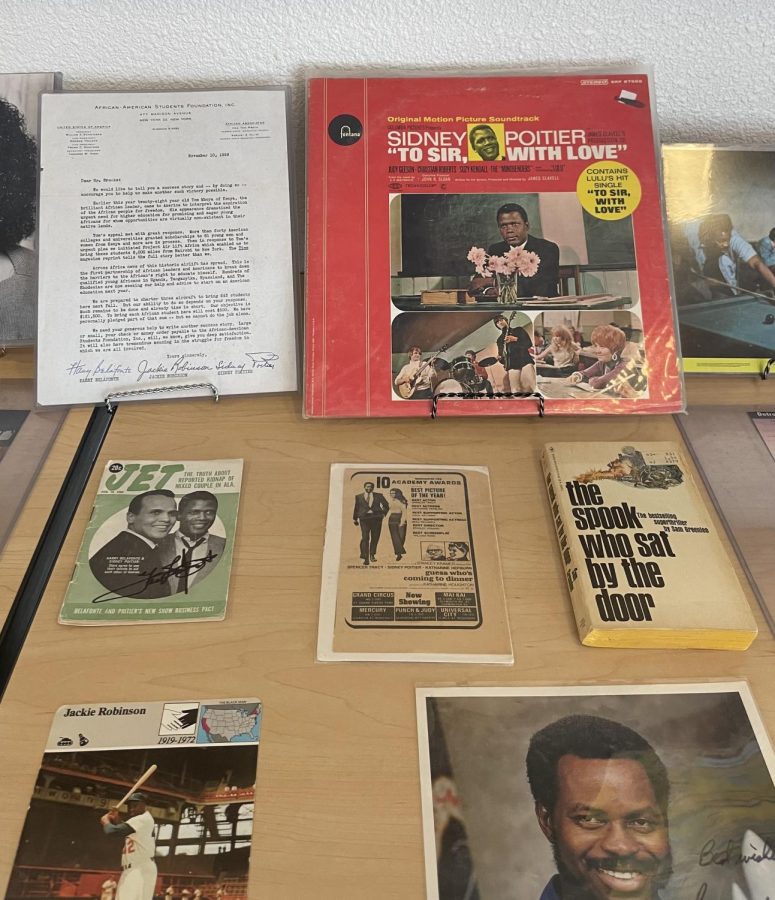

Tuesday’s pop-up museum was part of an exhibit El-Hakim called the “signature series,” referring to several artifacts on display that featured signatures. According to him, nearly 200 artifacts were part of the show.

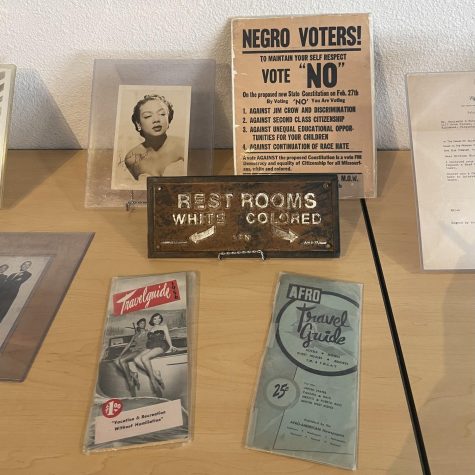

Among those were documents, letters, records, CDs, campaign buttons, posters, pictures, books and other objects that lined the tables in the community conference center where artifacts from the mobile museum were on display.

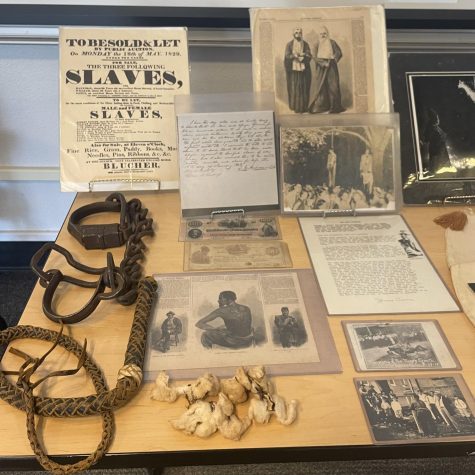

The items provided a glimpse into prominent eras of Black history, including the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Jim Crow era of segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and varieties of music, with an emphasis on hip-hop.

Students, teachers and community members applauded the traveling museum and El-Hakim’s presentation.

“I think it’s good that the school brought these artifacts to us,” said Ella Xu, a 20-year-old chemistry major at DVC. “I learned a lot about Black history and how it connects to us today.”

Another museum attendee, who chose to remain anonymous, said, “I am happy that [the museum] is on campus. It’s a reminder of our history in America and how important it is to keep fighting for equal rights.”

As part of his visit to DVC, El-Hakim held a presentation where he explained to students and visitors why he had included specific artifacts in the museum, and the underlying messages behind them.

His intention, he said, was to “keep it real” by showing often under-recognized aspects of Black history – not only the positive examples that are often discussed in history classes, but also unglorified parts of the past that often go overlooked.

While the inclusion of graphic pictures, racist ads, and books that “mock and dehumanize” Black people may be unsettling to view, El-Hakim said they reveal how deeply rooted racism remains in America, and help “fill the gaps in the history books.”

“That’s a part of history that people don’t talk about,” he said. Instead of turning a blind eye, El-Hakim hopes people can make connections to that history based on their lived experiences.

“I want people to find activists within themselves and address social justice.”

During his presentation, El-Hakim also addressed the significance of the hip-hop portion of the museum, explaining that “the power of hip-hop culture” gave artists the ability to “define and rename themselves.”

He provided specific examples of famous artists such as Dana Owens, who branded and defined herself through her hip-hop music and is most famously known as Queen Latifah.

“Hip-hop gives [Black artists] the space to claim who they claim to be,” said El-Hakim, “as long as they show and prove it’s who they are.”

He went on to explain that some of the bold decisions Black artists took in their work helped “raise the consciousness of people,” which led to important conversations about racist ideologies.

El-Hakim expressed a simple yet profound goal for the mobile museum.

“My intention is to teach students to think critically,” he said. “Dialogue is supposed to happen so we can walk away with a better understanding of each other.”