Diablo Valley College is no stranger to vandalism on its school grounds. Occasional written comments, questions and doodles appear on campus every semester. From outside benches to classroom desks, cases of vandalism get regularly reported at DVC, , a lot of which is racist or threatening.

In an incident in Spring 2023, for example, two sets of racist graffiti targeting the Latino and African American communities appeared on school grounds, leading to police involvement and a statement issued by DVC President Susan Lamb.

But more recently, a series of seemingly empowering and positive messages have caught students’ attention. In the last week of February, three anonymously written texts appeared in the women’s restroom of the Communications Building. According to some who saw the messages, the anti-colonial and anti-discriminatory themes are per haps what stand out most from past graffiti.

haps what stand out most from past graffiti.

The first note read, “YOU R ON AMERIKKKA US TURTLE ISLAND” in bright pink marker, signed with a beetle at the bottom. Two other pieces of graffiti, which read “Free the people” and “I love u, don’t allow them 2 make u doubt your voice,” appeared in the same restroom, written in the same pink marker and signed with the same beetle.

In the aftermath, the wall scribblings have sparked conversations as to whether they are justified – with some students seeing them as vandalism, and others admiring what appears to be a new form of protest art on school grounds.

The messages struck a chord especially with Danika Ajari, a first-year communications major.

“It’s very different than the usual graffiti, which tends to be rude or random art. It’s nice that it’s uplifting,” said Ajari, who as a Filipina said she sympathized with the messages, due to the experience of historical struggles against colonialism in the Philippines.

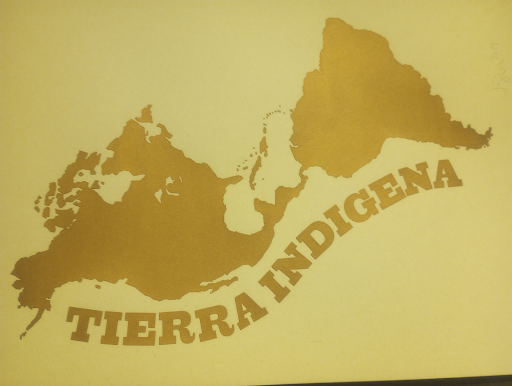

“I agree America is stolen land, so we are on Turtle Island,” she added, referencing the name given by various Native groups to the landmass of North America.

However, not everybody was as impressed. Another student, who wished to remain anonymous, stated, “at the end of the day, it’s still just bathroom graffiti.”

“They probably could try other ways of protest instead of writing on restroom walls that will need to be cleaned,” the student said.

The origin of the term “Turtle Island” is still being debated by researchers. Several Indigenous tribes, particularly the Mohawk people, used the name to describe the North American continent because of various stories of a turtle that holds the world on its back.

It’s not just students who are discussing the unique graffiti. Dr. Dani Cornejo, an ethnic studies professor at DVC, who is himself of Indigenous (Mapuche nation) and Latin American roots, said the vandalism invites people to ask some basic questions.

“What is vandalism? What is graffiti? It’s the voice of the unheard,” Cornejo said. “It’s people who don’t believe that they have a voice in public discourse, so they opt to write their perspective on a wall.”

Cornejo detailed his upbringing as a child of exile. His father, of Chilean descent, faced political persecution as a result of the CIA-backed Chilean coup d’etat that brought the dictator Augusto Pinochet to power in 1973. Like many others at the time, Cornejo’s father was forced to leave his native country and flee to the United States for safety.

In a recent interview with The Inquirer, Cornejo emphasized the importance of context when making a judgement about the graffiti and its potential meaning.

“The territory we now call the United States has not always been the ‘United States,’ it was Indigenous land before. We are unequivocally on stolen land, and that land was stolen through a white supremacist capitalist project,” Cornejo said. So, “what is the context that led somebody to write that?”

In his view, this form of messaging — unlike more typical, superficial comments or tags that appear as graffiti — “goes beyond self-expression,” distinguished by its more political undertones.

Cornejo recalled some of the more racist recent incidents of graffiti on campus, like several years ago when members of the far-right white supremecist group Nation Europa recruited people on school grounds, and individuals affiliated with the group allegedly left racist graffiti on school property.

The behavior led to involvement by DVC’s Black Student Union (BSU) club, which spoke out against and raised concerns around the issue. According to Cornejo, their voice inspired a more serious demand for Ethnic Studies classes on campus.

Further addressing the political message of the Turtle Island graffiti, Cornejo drew a line to the country’s political and economic system based on capitalism.

“The easiest metaphor for it is if you look at a tree, a capitalist will say, ‘How do I cut it down to sell off the wood to make profit for myself?’A socialist or communist will still cut down the tree to sell off the wood and redistribute the profit amongst everybody,” he said.

However, “An indigenous person leaves the tree alone, it provides shade and fruit, you don’t need to mess with it.”

Cornejo said such a worldview is rooted in the “Natural Law” perspective that is traditionally shared among Native American cultures.

The recent graffiti has since been erased from the restroom wall. But the discussion about its controversial form of protest, somewhere between artistic expression and property defacement, remains.

John Rodriguez • Mar 20, 2025 at 10:08 am

I like this story.