It is a closet with nothing more than a curtain for a door.

You think to yourself, “If I was a bad guy, I’d be in there.”

You push the curtain aside, and two gunshot rounds whiz by your face.

He just tried to kill you.

This is the guy you’ve been looking for.

Rather than killing him.

You grab him, throw him to the floor and detain him.

For 18 months, U.S. Army Spc. Niccola DeVereaux was on active duty in Iraq before returning home in 2006 and enrolling at DVC two years later.

But the Army is sending him back for another 15-month tour of duty, beginning next month, unless he gets a reprieve.

“This will completely decimate my life,” DeVereaux, 25, said. “Basically they have given me a prison sentence.”

It’s been five years since he first went to Iraq and another year since basic training at Fort Benning, Ga.

“I used to be able to run two miles in around 13 minutes,” DeVereaux said. “Now, if I even say the words, ‘two miles,’ I get tired.”

DeVereaux, who is studying art illustration, said it was difficult to adjust to civilian and college life after coming back from combat.

He couldn’t believe how casually some students take school. He would see someone miss class or send text messages on a cell phone and be shocked at the lack of discipline.

But the disbelief has begun to fade.

“The further away from the Army you get,” DeVereaux said, “the more you just act like a regular student.”

While in Iraq, he didn’t have to worry about anything, he said.

“The Army gives you money for college, food to eat and puts a roof over your head,” he said. “You live in a bubble.

“No bills. No girlfriend. No bullshit.”

And there are few choices.

“Your biggest choice is what to eat for lunch, the red slop or the green slop,” he said.

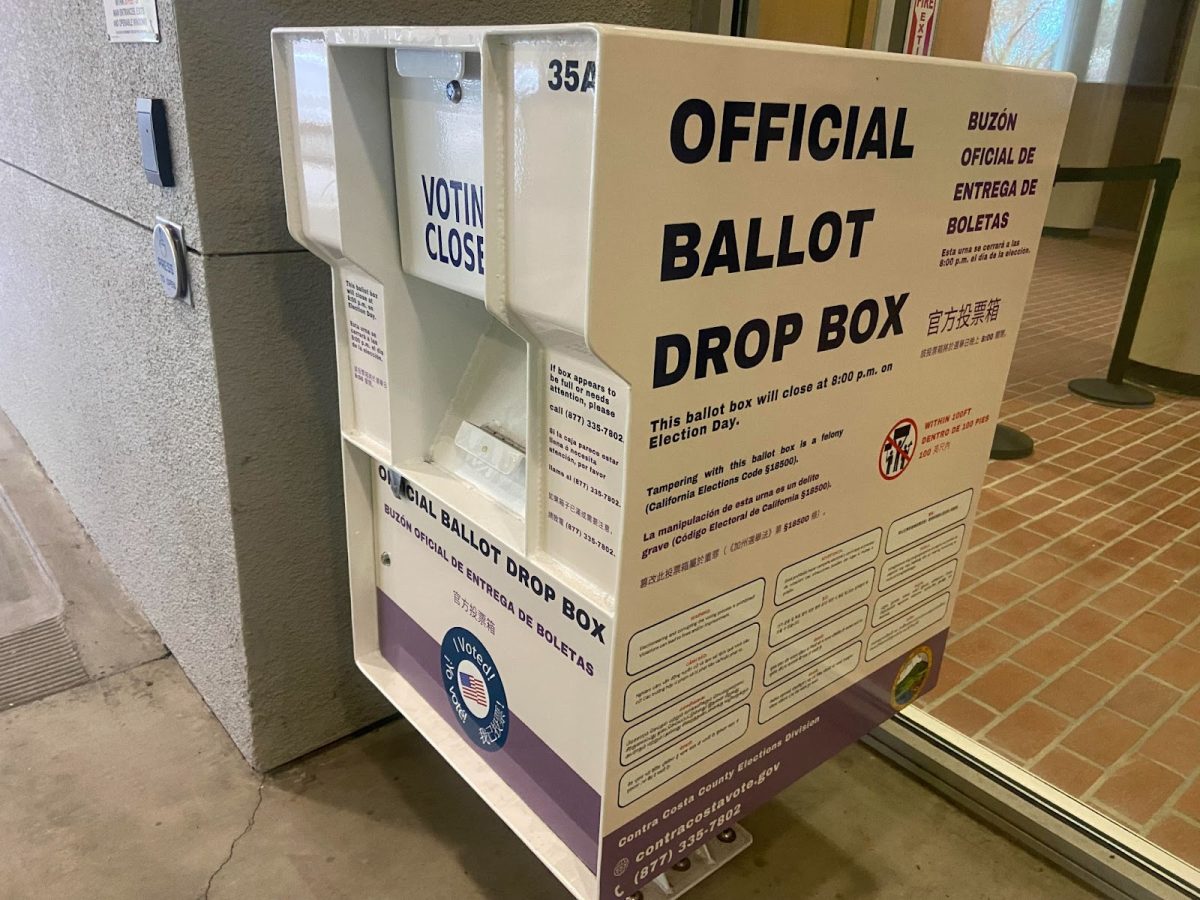

At age 20, DeVereaux was deployed as part of “Operation Iraqi Freedom.” Saddam was out of power, and voting had just started for the new president of Iraq, with women participating for the first time.

The U.S. military set up two voting sites, one of them a decoy, both blocked with razor wire and large cement blocks.

DeVereaux was on the roof of the real site when they started taking mortar and sniper fire. Manning the radio from a vantage point that allowed him to see everywhere, he radioed the lieutenant they needed to return heavy fire.

The lieutenant relayed the message to the fire team. But over the next eight hours, he ordered DeVereaux to make the calls direct.

He described what happened:

We are taking fire from everywhere.

The U.S. Army has plenty of firepower – four Stryker vehicles, and fire teams, all fully armed.

I assisted in commanding the whole operation from the roof because I am the only one who can see anything.

All the while, the people come in and vote.

Bullets flying over heads, they still come.

All women, no men.

From the roof, I see the women hold up their finger with ink on it.

Proof they voted.

For calling in the fire team from the roof, DeVereaux was awarded the ARCOM medal.

“I didn’t think much of it, and now in retrospect it’s kind of cool,” he said.

Six months later, DeVereaux turned 21. There was no alcohol with which to celebrate.

“You don’t want to drink over there,” he said. “People’s lives are depending on your mental state.”

DeVereaux related another vivid memory:

He doesn’t fit the image of a terrorist.

He is a well-dressed guy who worked at an Internet café on the base, where soldiers pay him $1 an hour to use his computers. He speaks English.

He is crying.

He speaks with me and says he felt like he was being stiffed. He wasn’t making enough to support his family.

Still crying and about to die, he tells me he didn’t see any progress; after the U.S. invasion, nothing good was happening.

Someone had offered him an opportunity: Kill an American and we’ll give you prize money.

Even then, DeVereaux said, he didn’t hate this man, who was shot by U.S. troops before he could shoot them. He was disgruntled and “an easy pick” for a terrorist cell.

“This guy is just a family guy, trying to make things meet in a war-torn country,” DeVereaux said. “Even though he was trying to shoot at us, you couldn’t help but feel bad for the guy.”

Now, unless his appeal goes through, DeVereaux must return to Iraq and go through all of it again.

And what he will miss most about being a college student?

“I don’t know,” DeVereaux said, adding after a pause, “Not killing people”