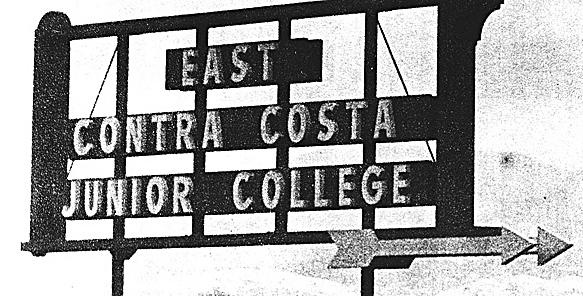

The Inquirer celebrates 60 year history

()

October 13, 2009

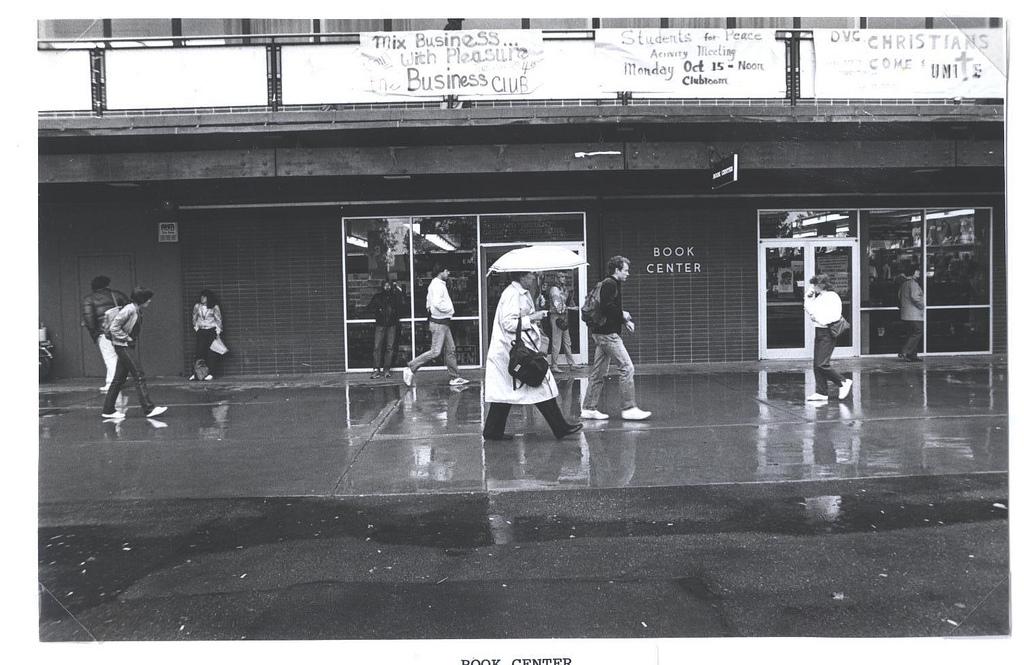

That first issue on Sept. 28, 1950 didn’t look much like a newspaper. It was little more than a single sheet of paper folded in half with a hand-drawn banner.

But then East Contra Costa Junior College didn’t look like much of a campus either.

Quonset huts and large red and white tents served as the first crude classrooms. And the students – only 300 that first year – roasted in September and then slogged through mud when the rains came.

“We thought of ourselves as pioneers,” recalls Pat Keeble, who joined the student newspaper in 1955 and later became its editor in chief. No longer the “East Contra Costa Junior College Newsletter,” the “Viking Reporter” was now a tabloid-size newspaper with faculty adviser David P. Marin, formerly of the Associated Press.

Although she would later work for United Press International (a competitor of the Associated Press at the time) and then as the long-time bureau chief in Martinez for the Lesher newspapers, Keeble still remembers the terror of her first interview.

But when she saw her byline and story on page one, there was no turning back.

Keeble remembers announcing, “This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Soft-spoken and shy, she had also discovered an amazing truth about being a journalist.

“You can be terribly nosy,” Keeble says. “You can ask the most outrageous questions, and if you’re skilled about it and you don’t go overboard, you’ll get answers.”

Every week the newspaper staff would gather around the kitchen table in Keeble’s house to write headlines and to layout the paper.

“My mother would make coffee and [we’d] have some cookies,” she remembers.

The staff worked until 10 or 11 p.m. when someone would finally drive the finished product to the printer in Pittsburg.

Sheila Grilli remembers more than just the cookies.

“Pat had brothers and a sister and all these people hanging around, and her mother,” Grilli says. “There even was a monkey for a period of time.”

When Grilli succeeded Keeble as editor in chief, laying out the paper at someone’s house abruptly ended.

At that point, the entire newsroom was stuffed into a Quonset hut, which the newspaper shared with a biology class.

“We had this little space that could have been 10 feet wide,” Grilli says, sharing memories with Keeble of those long-past years on a recent afternoon in her small Martinez bookstore.

After DVC, Grilli went on to work at the “Martinez Reporter” and spent five years as adviser to the Clayton Valley High School paper and yearbook before eventually buying the bookstore. She currently serves as president of the Contra Costa Community College District Governing Board.

In the early years, the “Viking Reporter” covered campus sports, dances, club events, student government and much more. It also had a gossip column, the “Scandal Sheet” and a long-running cartoon, “Little Man on Campus.”

When Gary Bogue joined the staff in 1956, he wrote a “Dear Abby”-type column in which he gave tongue-in-cheek advice under the pseudonym, “Gabby Male Van Viking.” It ran each week with a picture of Bogue dressed incognito, a mop draped over his head and his face partially obscured.

He also wrote a gossip column, “Overheard…From Car to Caf,” in which he anonymously repeated conversations overheard around campus.

“Nobody knew who was writing it,” Bogue recalls. “And so I had a lot of fun, because I’d pick up stuff…and [then] be there to snicker to myself when they were raging and ranting about something that gotten printed in [the column].”

Having never lost his taste for column writing, Bogue still writes “Pets and Wildlife,” a popular question-and-answer column he started at the Contra Costa Times in 1970s.

At the “Viking Reporter,” in the mid 1950s, Sal Veder, a professional photojournalist, helped the greener members of the staff.

“I shared some of my own experiences, and did some dark room training,” he recalls.

At the time, Veder was also working at the “Concord Transcript” (which later became the Contra Costa Times) and later went on to work at the Associated Press for 32 years as a photographer and a photo editor.

During his time there, Veder won a Pulitzer Prize for his photograph of a POW returning home from Vietnam running towards his family on a Tar Mac.

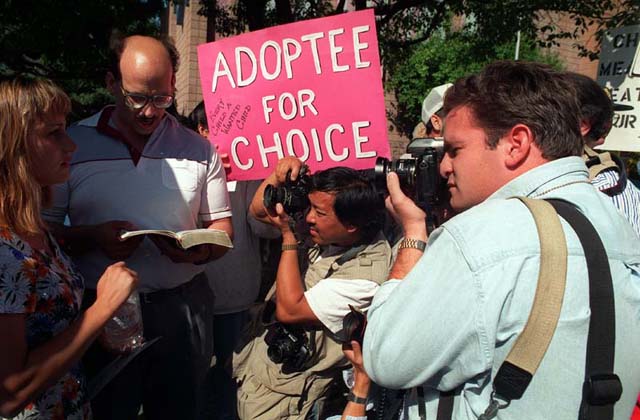

The 1960s and 1970s was a time of change and upheaval on college campuses across the country. At DVC, student protested against the Vietnam War, faculty members fought against the draft and speakers were brought to campus with new ideas, such as a psychologist who promoted the benefits of LSD, according to the DVC 40th anniversary book.

During Brian McKinney’s years as faculty adviser, from 1969 to 1976, the student newspaper once again changed its name, becoming “The Diablo Valley College Enquirer.”

“It was an exciting time for student newspapers,” McKinney says during an interview at his Orinda home. “There was a lot of hoo-ha going on, particularly on student newspapers.”

Inquirer alum Debbie Carvalho, who was on staff from 1970 to 1972, describes McKinney as a “pretty hip dude for his time.”

“He was pretty laid back…[and] definitely a product of the ’60s,” she says during an interview in her cubicle at the Contra Costa Times. “He pretty much let us stretch and do what we wanted to do.”

Before coming to the Inquirer, McKinney had worked on his high school and college newspapers and edited the newspaper at Castle Air Force Base.

During this time, “The Enquirer” stirred considerable controversy with its news coverage.

McKinney recalls the time an Enquirer sports editor rode back from a basketball game with the DVC team only to witness players smoking marijuana in the back of the bus.

Viking athletes smoking pot became part of his subsequent story on the game.

All hell broke loose.

The basketball coach insisted on a meeting with McKinney and the sports editor in DVC President William Niland’s office.

“You shouldn’t have printed that story,” the coach said angrily. “Why didn’t you come to me?’

McKinney remembers retorting: “It’s not the job of the newspaper reporter to report to the government. The job of the newspaper is to print the news. This is news.”

Niland supported the “Enquirer,” but the debate loomed large in people’s memories long after the student journalists and athletes had departed to four-year schools.

Controversy also dogged the “Enquirer” in its coverage of DVC’s student government, particularly when the newspaper uncovered scandal in the Associated Students of DVC.

During this time, the lines between the newspaper and the student government sometimes blurred, with current and former Enquirer editors also serving on the ASDV board.

After Carvalho left the paper, she ran for ASDVC president and admitted to stuffing the ballot boxes to “prove it could be done,” according to a 1972 front page article “Ballot boxes stuffed, election thrown out.”

Another series of articles from 1971 reported on an ASDVC board member who was censured and made to stand for an internal trial. The “prosecutor” was an ASDVC board member and managing editor of “The Enquirer.”All charges were later dropped against the board member because proper protocol wasn’t followed when he was charged.

However, a month later the Enquirer reported that he was suspended for “blatant and overt attempts at censoring the Enquirer,” among other things.

“I don’t think they [the student council] liked that we were writing about them,” Carvalho says.

During McKinney’s years as adviser, the ASDVC paid for the Enquirer’s printing and supplies budget. But he who controls the purse strings can wield a pretty powerful stick. And McKinney remembers the day it came crashing down.

“The student council decided, ‘Why should we pay for this guy to whack away at us? Let’s just cancel them out.'” McKinney says. “So they took away all of our funding.”

“For about seven weeks, we were printing on mimeograph machines. That was really painful.”

McKinney said the “Enquirer” staff tried to get the ASDVC to change its mind, but to no avail. Fortunately the district stepped in and provided some funds for printing.

“Newspapers are the national enemy of government,” McKinney says.

In response to the ASDVC withdrawing its financial support, the Enquirer ran a front page story with the headline, “Fastest freeze in the west: The Enquirer and its off -again on-again funds.”

Aside from student government, there were problems just getting the paper out each week.

“We didn’t have our own dark room, so we had to use the one used by photography students, McKinney says. “Sometimes our guys couldn’t get in there and had to wait.”

Carvalho, who became editor in chief during her time at the “Enquirer,” later graduated with a degree in journalism from San Jose State, covered sports for the Contra Costa Times and is now its TV Times/copy editor.

McKinney, who gave up advising to become a full-time English professor at DVC, still becomes passionate when talking about importance of the student newspaper and its “watch-dog” role, whether “Inquirer” is spelled with an “e” or an “i.”

“[Without it] you’ll lose a very important eye on what’s going on for students, faculty, administrators and staff,” McKinney says. “They all need to know what’s happening, and the only way they get to know is by reading the newspaper.”