Professor Nelson Maldonado-Torres Makes the Case for Ethnic Studies

March 24, 2021

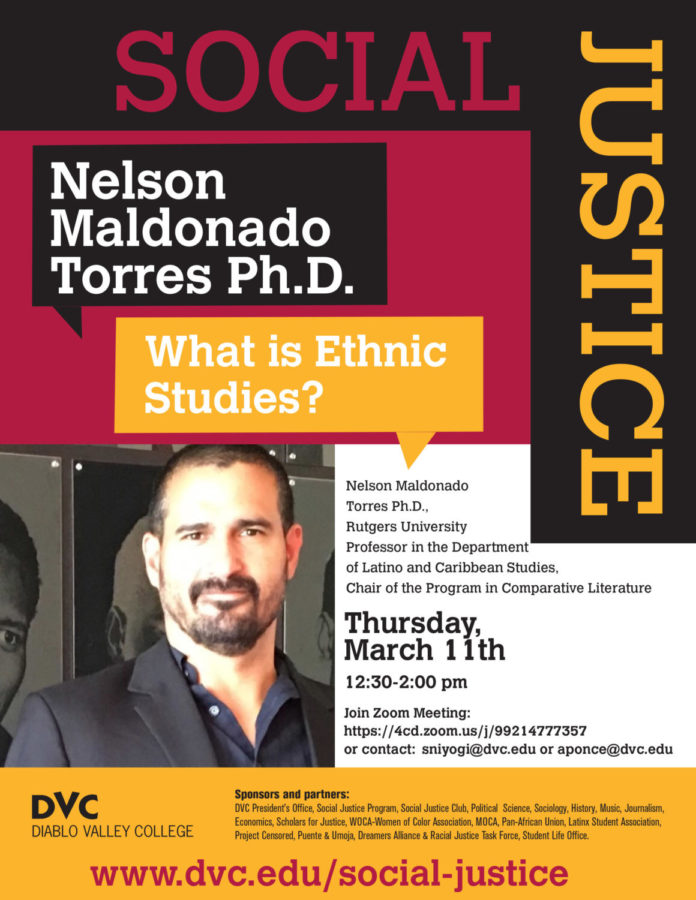

On March 11, more than 150 people attended a Zoom talk hosted by Diablo Valley College’s Social Justice Program, where they heard guest speaker Nelson Maldonado-Torres jump without fanfare into his central thesis.

“Ethnic studies is one of the most, if not the most, important academic formation in the 20th century,” said Maldonado-Torres, a professor in the Department of Latino and Caribbean Studies and the Comparative Literature Program at Rutgers University, and author of Against War: Views from the Underside of Modernity.

Maldonado-Torres argued that during the 1800s, while Western universities became less religious and more focused on science and secular studies, they failed to develop a sufficiently anti-racist curriculum. Schools across the United States still lack in this area, Maldonado-Torres said, and stronger ethnic studies programs are the solution.

As recently as August 2020, this line of reasoning compelled Californian lawmakers to pass AB 1460, which requires California State University students to take an ethnic studies class to graduate. According to CSU’s general education requirements, these classes must discuss either the African American, Asian American, Latina and Latino American, or Native American experience while also meeting criteria that teaches students how to critically analyze identity.

Around 80,000 California community college students transfer to CSUs annually, meaning the policy will impact what some DVC students learn as well. And Maldonado-Torres believes that is a good thing.

At their best, he said, these classes leave a lasting impact, changing how students think during and after college. “We need more and more people informed with this critical knowledge, so they can make a difference,” he said.

But to achieve those results, Maldonado-Torres said these programs need to be more hands-on, engaging students outside the classroom. “From the beginning, ethnic studies was never a pure academic exercise. When you look at the main examples, [Frantz] Fanon, Malcolm X, or Angela Davis … these are folks who are being political in the way they produce knowledge,” he said.

According to Maldonado-Torres, ethnic studies classes should encourage students not just to study, but to get involved with their community. In his view, the curriculum could be structured around students and teachers working together to create real-world change.

Furthermore, Maldonado-Torres said that universities have to avoid “juniorizing” the field. For example, instead of housing these classes in a social science department, Maldonado-Torres believes that ethnic studies programs should be treated independently – like at San Francisco State University’s College of Ethnic Studies, where departments like Asian American and Indian American studies are separate from each other.

“It’s not by accident that ethnic studies, as a formation of insurgent knowledge in this space, always has trouble finding adequate recognition and support,” he said.

Maldonado-Torres also highlighted the importance of professional development geared towards faculty. Noting that some professors aren’t specifically trained to teach ethnic studies, but are asked to do so anyway, Maldonado-Torres suggested that colleges offer more learning opportunities for professors to expand their curriculum and address systemic racism head-on.

“The faculty themselves have to be educated and introduced to some major aspects of what ethnic studies is, because, if not, they will be re-extending the imperatives of the 19th century university,” said Maldonado-Torres, “only thinking of people of color as objects of study.”

Maldonado-Torres said, “In the United States, where in the 21st century there is a massive demographic shift that is generating a different country, it is clear that a university premised on 19th century foundations, concerns, and questions is no longer, and has never been, enough.”