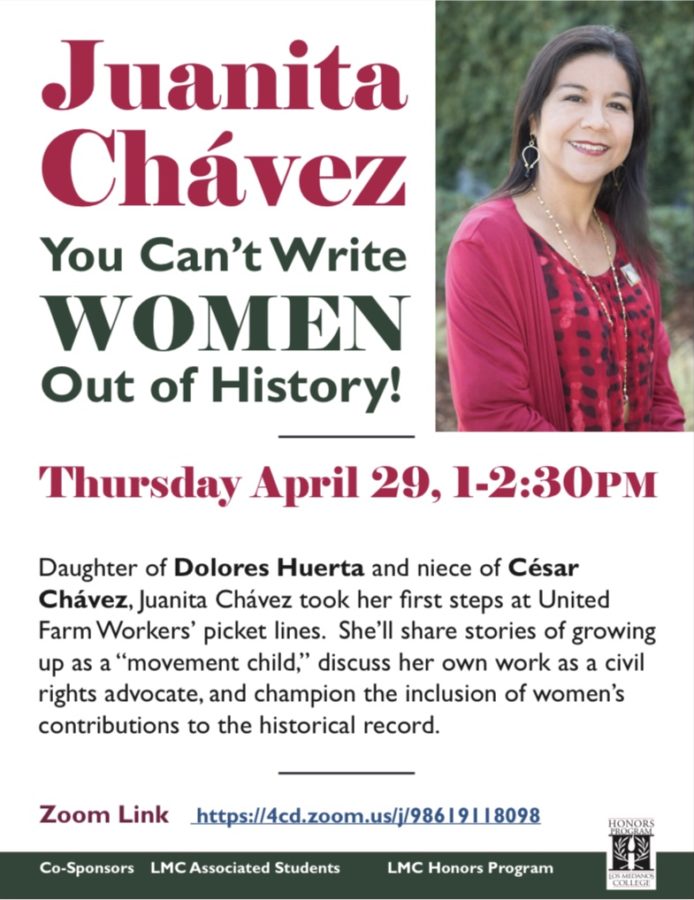

Juanita Chávez: The Daughter of an American Labor Icon Speaks Out on Social Justice and Women in History

May 12, 2021

Cesar Chávez: A name that many Americans associate with civil and workers’ rights. But conversations about Chávez and the strides he made in securing rights for low-income farm workers would be incomplete without the mention of his passionate co-organizer, Dolores Huerta.

Chávez’s niece and Huerta’s daughter, Juanita Chávez, headlined an April 29 talk hosted by Los Medanos College, entitled “You Can’t Write Women Out of History!”, which centered around Chávez’s upbringing on the United Farm Workers’ picket lines, her work to protect and expand civil rights, and the importance of recognizing women’s contributions to history.

Her mother, Dolores, now seen as an icon for workers’ rights, was considered “a crazy lady with radical ideas” in her time, Chávez pointed out, and provided a prime example of the power of women to shape the world around them. “Dolores has a huge hope… for humanity. It may never be perfect, but it will always be getting better,” Chávez said.

Chávez has left her own mark on the social justice landscape through her longstanding commitment to activism and as a teacher in inner-city public schools in Los Angeles and San Francisco. She has served on the Dolores Huerta Foundation’s board of directors since 2003 and is currently its development director.

According to the foundation’s website, Chávez and the rest of the staff are “on a mission to inspire and organize communities to build volunteer organizations empowered to pursue social justice.” For many years, they have been doing just that.

While teaching at Mission High School in San Francisco, Chávez helped develop the Gay-Straight Alliance for students. About 20 years later, it remains one of the strongest groups on campus. “We had created a safe space for LGBTQ students to feel at home,” she said. “We knew that it had to be done.”

Inclusion is a theme that has wound its way through much of Chávez’s life. Her early years spent on picket lines and marching for the union rights of farm workers stemmed from her mother’s belief that children should be a part of the movement. As a girl, she recalled, her participation at protests “just seemed natural, the way we were living out life.”

As a child of a parent intensely involved in the farm workers’ fight, she admitted it was “a little bit rough on us as kids” dealing with frequent parental absence. But, “as an adult, I’m grateful we had that experience,” said Chávez.

There were other challenges along the way. Growing up, Chávez faced discrimination at school because of both her race and her family’s poverty. Teachers referred to her uncle, Cesar Chávez, as a communist. Her own brother was expelled for disputing a teacher’s lesson about Columbus discovering America.

“It was a rough environment we grew up in,” she said, though she matured with the knowledge that “there are so many situations like mine and worse, [with] blatant discrimination that is unreported [and] unaddressed.”

Her early experiences encouraged Chávez to pursue a career in education. Living within walking distance of the schools at which she taught, she strived to provide an alternative view of history for her students, who mostly came from immigrant families. While teaching at diversified Mission High School in San Francisco, Chávez dealt with run-down school buildings and even once held a lesson about precipitation as rain leaked into the classroom from outside.

Despite the obstacles, Chávez said she made it her mission to foster dignity in her students by teaching them about the many contributions of their Indigenous ancestors. “The exalted missions, they were built by slave labor, pretty much,” she said.

Chávez believes classrooms, steered by the right principles, have the capability to become vehicles for social justice. “We have to have ethnic studies in our schools. That’s really one of the main ways that we can rid our society of this toxic racism,” she said.

In Chávez’s view, ethnic studies shouldn’t be optional but should instead be taught in schools from kindergarten onward. If students are aware of the contributions their relatives and ancestors have made to the fabric of America, they can use that knowledge to combat discrimination.

Conversely, she added, if the only message conveyed through the curriculum is one of ancestral slavery, that can damage students’ mindset. The same can be said for school curriculas’ failure to include the historical contributions of women.

Chávez explained that until recently she was unaware of the ongoing debate about whether or not to include Dolores Huerta in the state-sponsored curriculum for schools. She called the controversy an “outrage.”

“When I learned about it, what a badge of honor. If they are trying to burn your book… you are doing something pretty powerful,” she said, adding that she “feel[s] angry for the students who are being denied that knowledge and that history.”

Only when girls and women escape from the victim mentality, which fosters insecurity about their abilities, can they realize their full potential and contributions to society, Chávez said. The seeds of this detrimental type of thinking are planted at home and in childhood: for example, the encouragement of little boys to roll around in the dirt and work through their fears differs from the neat, clean and coddled expectations of little girls.

“It’s a big thing,” Chávez said, remarking that little girls need to be encouraged to speak up early in their childhoods. “If we look at our own behavior, how do we treat the girls different from the boys?” To grow into strong women, girls need to face challenges while they are young, she added.

Asked why she thought her mother’s strides for social justice have been so closely associated with the work of men, Chávez reflected on the different social landscape of the 1950s through the 1970s, when Huerta was an activist. “My mother’s goal has never been recognition,” she said.

Noting Huerta’s Catholic upbringing, which taught her that it is a sin to have pride for good deeds, Chávez also pointed out the need for “women to uplift their stories.” If there is limited space for discussion about Latino activism, it will likely be dedicated to Cesar Chávez, with Huerta and her accomplishments mentioned as a footnote, Chávez said, emphasizing her mother’s lifelong focus on organizing and bringing people together for the cause of social justice.

Taking cues from her mother, and ensuring that the nation’s schools remain places that embrace as well as enable students of color, is a cause that Chávez holds close to her heart. In 2015, the Dolores Huerta Foundation along with parents and students filed a lawsuit against the Kern High School District in Bakersfield.

The suit detailed the disproportional suspension and expulsion rate of Latinos in the district, which stood at 400 percent the rate of Anglo students’ suspensions and expulsions. The judge found the school guilty of discrimination and, as a result, the district was required to reform its actions by employing implicit bias training and diversifying its staff and leadership.

“It’s not just what teachers can do in the classroom. It takes pressure from the community for a school district to reform policy,” Chávez pointed out, calling the case a victory for the foundation.

Many people ask: How can we get more dialogue about social justice in the classroom? Chávez responded: By speaking about families facing the dilemma of paying bills or putting food on the table. She acknowledged the strong pushback by those with wealth and resources who wish to maintain the status quo.

But she pointed out that rather than furthering the “us versus them” argument and attacking the 1 percent, the discussion should revolve around struggling citizens – like mothers suffering without heat in the winter. “We need to make those conversations more universal,” she said.

Chávez added that citizens can get involved and help decide which parts of their community need help the most. For example, when redistricting occurs, members of affected communities can stand up and prevent unfair lines from being drawn. “It’s upon us, who have the privilege of education, of being English speakers, who have time,” she said. And when the needs of districts are adequately met, more equitable funding for schools can result.

On the issue of anti-racism inclusion in higher education, Chávez advised teachers to get involved in protests, strive to get elected to boards that make decisions, and advocate leadership election for those who share their interests. When she witnessed and tried to call out injustice as an educator, Chávez recalled that it led to her being targeted with subtle retaliation. “I felt it [was] very challenging to make change from within,” she said.

Now, helping steer the foundation named after her celebrated mother, “I wake up passionate about the work I do every day,” she said. Her lesson for today’s students confronting racism and classism: continue building self-esteem and believe in yourself.

“Despite what they think of me being poor and brown, I am going to be someone and succeed.”

The Dolores Huerta Foundation will be holding its 91st birthday celebration online for its namesake activist on May 22. Proceeds from the event will benefit the creation of the Dolores Huerta Peace and Justice Cultural Center.