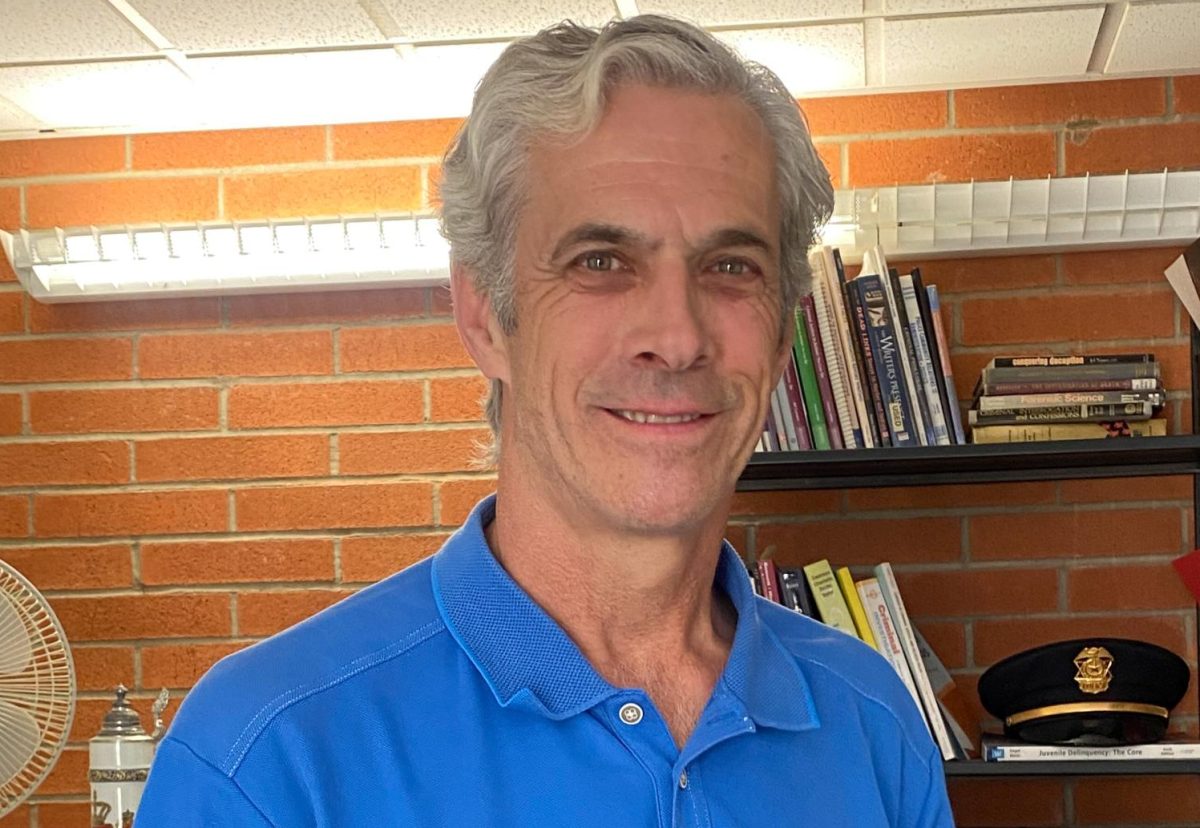

“Shock and horror and disappointment” is how Matthew Morrissey, chair of the DVC Administration of Justice program, described what he felt about the federal and local corruption charges brought last month against 13 Antioch and Pittsburg police officers.

The charges stem from an investigation of a series of racist text messages sent earlier this year by law enforcement members from those cities, and made national headlines after officers had their homes raided by FBI agents on Aug. 17.

The officers face federal and local charges of fraud, steroid distribution, obstruction of justice, and civil rights violations.

“I’ll say most of us, in fact all of our instructors, our administration, our career professionals, we’re all either full careers in the criminal justice field or policing, or some are currently still working, and this is not what we stand for,” said Morrissey.

Five of the 13 officers — Timothy Manly Williams, Ernesto Juan Mejia-Orozco, Ben Padilla, Calvin Prieto and Andrea Rodriguez — are facing local charges of criminal conspiracy and bribery. Williams faces additional federal charges of obstruction of justice, and Mejia-Orozco faces federal charges of college and wire fraud.

All five officers appeared Sept. 13 for their first day of court in Martinez and pleaded not guilty. They received follow-up dates to appear in court: Williams, Prieto and Rodriguez are scheduled for Oct. 19, and Padilla and Meija-Orozco for Nov. 6.

The charges represent the latest crisis for the Antioch and Pittsburg police forces in the past year alone. Former Pittsburg police officer Armando Maltavo is currently on trial for allegedly making illegal sales of AR-15 rifles, and former officer Mathew Nutt of Antioch is being charged with assault after allegedly using excessive force during a traffic stop on July 1, 2022.

The gravity of the recent charges, and their proximity to the DVC community, has caught many people’s attention.

Morrissey said he wants to see the school’s justice program produce more officers — and a culture of law enforcement — that stands up to corruption.

“You can’t just pretend you didn’t see it, or don’t say anything, because then you’re as responsible as that offending officer,” said Morrissey. “Culture is a really important part of learning why these bad deeds are happening.”

In a series of interviews with The Inquirer, DVC students expressed mixed reactions to the scandal that has engulfed both local police departments.

Economics major Fathima Abdul Gafoor in particular called for culture reforms. “The reason why this is happening in the first place is because of their co-workers not taking accountability,” said Gafoor.

“It’s just like friends protecting friends, that sort of thing — but on a federal crime level.”

DVC student Joshua Mix felt more conflicted about the issue. He said he wanted to see in-depth changes take place in the hiring process at police departments, but also acknowledged those processes can easily be sidestepped.

“How can you really [enforce reforms]?” Mix said. “People can lie and act like they want to be something they’re not.”

At the same time, DVC business major Brandon Nice said there’s too much focus on crime in bigger cities in the Bay Area, leaving smaller cities like Antioch and Pittsburg more susceptible to corruption.

“They’re kind of paying more attention to Oakland, San Francisco, Berkeley, even Concord,” said Nice, “but never really Pittsburg and Antioch.”

“I don’t think no one really holds those people out there accountable.”

The officers facing local charges could face up to four years in prison if convicted. Officers facing federal charges could see up to 20 years in prison with a $250,000 fine.

All defendants in the local case have posted bail and waived their right to a speedy trial, meaning it could be many many months until a verdict is reached.