On the night of Jan. 22, the first day of instruction for the Spring 2024 semester, the staff of the Social Sciences Center (SSC) received an email from the dean of social sciences, Obed Vazquez, stating that the center had overspent its year-long budget during the fall semester and needed to scale back on peer tutoring.

As a result, the SSC staff significantly reduced the work hours of their peer tutors and laid off all six of the center’s embedded tutors three weeks after they had confirmed their original tutoring schedule for the semester.

“It just broke everything,” said Ky Perbix, the senior lab coordinator at the SSC, located at Learning Center 105.

“Everybody had been told [their schedules] the week before classes—teachers, tutors, everything,” she said. “We had tutors last semester who were doing 25 [to] 30 hours a week – which is a lot, granted – but now they’re at 6 [hours].”

Perbix said the administration’s last-minute communication about the SSC’s budget overrun was particularly frustrating because the center’s staff had never been informed of their budget limitations in the first place.

“It has been terrible communication from top down,” Perbix said.

The news of the center’s overspent budget exposed the missteps, miscommunication, and misunderstandings that abounded as the administration adjusted to a relatively new budget system.

Tensions between administration and SSC staff escalated in early March, when the school’s vice president of equity and instruction, Joe Gorga, allegedly placed the blame for the center’s misspending on Vazquez in an Academic Senate meeting and in a subsequent meeting with an SSC tutor, according to adjunct professor of social sciences Nolan Higdon.

Higdon resigned from his position as SSC tutoring coordinator on March 11 in response to what he called the executive administration’s lack of transparency and accountability.

In an email sent to SSC staff, the dean and executive administrators, Higdon repeatedly criticized “the ineptitude of upper management” and wrote that the “budget problems and weakening morale at the Social Sciences Center are not [Vazquez’s] fault.”

“There was no budget communicated to the center before the Spring 2024 term began (not to mention the 2023-2024 academic year), and by the time a budget was communicated, we had already over spent the arbitrary amount set,” Higdon stated.

The Inquirer later learned that Vazquez was in fact aware of the budget since November, but even then, the center would have only had three weeks left in the semester to implement a more sustainable tutoring schedule.

The day after Higdon resigned, Gorga retracted his previous statements and formally apologized at an Academic Senate meeting.

“When [the budgetary] information is given to the deans, it was really my job to make sure that they understand that information,” Gorga said in an interview with The Inquirer. “So if there are any mistakes, ultimately that comes down to my shoulders.”

The Turmoil Unfolds

The Social Sciences Center has been fully operational since Fall 2023, making it the newest of six student centers that are scattered across the Pleasant Hill campus, offering peer tutoring, study spaces, academic workshops, printing services and free snacks for students.

Since construction began on the first student centers about three years ago, the centers hadn’t had well-defined budgets. This changed in the summer of 2023, according to Gorga, when the administration established new budgets, based on tutoring demand collected from student sign-in data.

Vazquez said the school’s executive administrators sent him the 2023-2024 budget for the SSC on Nov. 13, 2023, just three weeks before the end of the fall semester.

Vazquez did not immediately relay the budget information to the SSC. When asked his reasoning, Vazquez told The Inquirer, “I don’t know.”

Between December 2023 and January 2024, the administration implemented a new practice of reviewing the expenses of all the student centers from the fall semester in order to plan ahead for spring, according to Vazquez.

In its review, the administration found that the SSC’s fall expenditure was $34,000, exceeding its original $20,000 year-long budget by 70 percent, according to a document that was shared with The Inquirer in March.

Some SSC staff members criticized the center’s original budget allocation after learning that it was tens of thousands of dollars smaller than most other student centers. To Perbix, the budget limitations seemed to thwart the center’s efforts to boost student traffic.

“We’re trying to build [student engagement with the center], but it’s kind of like we’re just being chopped off at the knees,” Perbix said.

Vazquez said the SSC’s budget was smaller than that of other centers, because although the SSC attracted many students to the center by the end of the fall semester, student demand for social science tutoring appeared weak in comparison to the tutoring demand in other centers.

Vazquez added that the administration was “being gracious, saying ‘Yes, we want a tutoring program, but this is how much [money] we have for it.’”

According to the document shared with The Inquirer, the number of Fall 2023 tutoring sessions averaged between the Academic Support Center and the Arts, Communication, and Language Center was 355. Meanwhile, the average tutoring sessions averaged between the Math and Engineering Center and the Science and Health Center was 1,667.

In contrast, the Social Sciences Center reported only 55 tutoring sessions for the entire Fall 2023 semester, the least amount out of all the student centers.

However, this data likely underrepresents the tutoring impacts of the SSC, because unlike most other student centers, the SSC staff neither recorded the number of tutoring sessions held over Zoom, nor documented the student demand for embedded tutoring, according to Perbix.

The documentation of in-person visits was further implicated by malfunctions in the sign-in kiosk during the first half of the fall semester, Perbix said.

Overall, it’s been difficult to gauge the extent to which SSC tutoring was underrepresented, given that social sciences “didn’t really have a tradition of tutoring,” according to Vazquez.

Despite its historically low demand for tutoring, and unaware of its budgetary constraints, the SSC hired 14 tutors when it opened the doors as an in-person facility in the fall, increasing its offerings from a single discipline to 11 different disciplines.

Gorga said that since the concept of social science tutoring and the center itself were relatively new, the administration expected the center’s student traffic and tutor offerings to stay the same compared to the previous year, but this was not communicated to the dean or the SSC staff.

“I think that there might have been [an] assumption that they could increase the amount of [tutoring] hours significantly compared to the year before,” Gorga said. “So I think it was just a misunderstanding.”

According to the SSC’s tutor schedules, two individuals employed as both embedded and peer tutors in the SSC worked 27.5 and 28.5 hours a week in Fall 2023.

According to Gorga, embedded tutoring was originally designed to promote student success in transfer-level English and math courses, and given that it’s an expensive tutoring model, Gorga said the college “really can’t afford to have all classes using embedded tutoring.”

The pair of embedded tutors were going to continue in their positions in Spring 2024, but after the budget over-expenditure was announced, their embedded tutoring jobs were cut and their workload decreased to six hours a week each.

Students Call For ‘Better Transparency’

For 21-year-old English major Abraham Allison, the sudden loss of his embedded tutoring job for an ethnic studies class affected him beyond its financial implications.

“I genuinely loved that position,” said Allison. “I want to be a teacher, I want to be a professor. So that’s where it impacts me personally, too, [because] I’m not getting the experience I want.”

He added, “I was just really sad, genuinely, to see that I wasn’t continuing.”

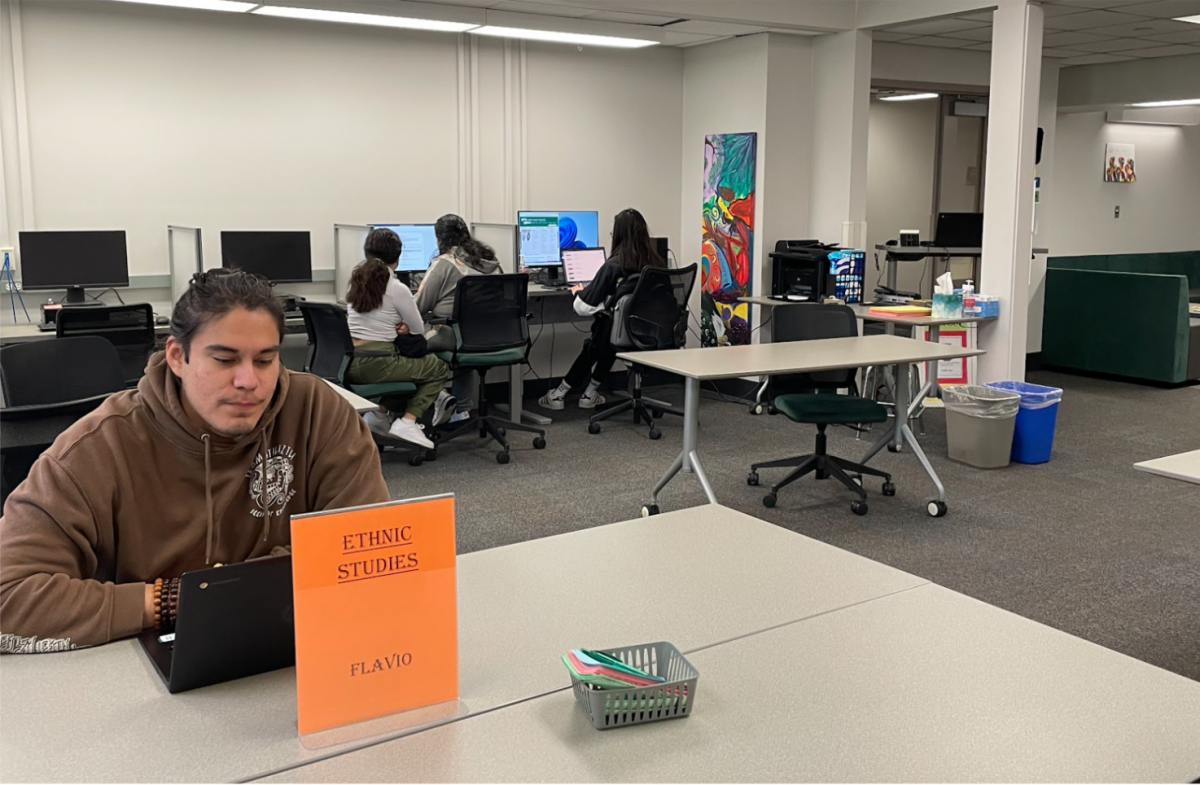

In response to the SSC’s last-minute tutor adjustments at the start of the semester, Allison decided to take action alongside Flavio Cuevas, a 20-year-old English major who lost his job as an embedded tutor and experienced cuts to his peer tutoring hours.

Allison and Cuevas gathered 131 signatures from student employees and peer allies to petition the DVC College Council to “provide better job security, provide better transparency about hours, [and] provide better transparency about the [student center] budget.”

This was followed by a private meeting on March 5 between Allison, Cuevas, DVC President Susan Lamb and Gorga. According to Cuevas, Lamb and Gorga expressed their sympathy for the affected tutors, and handed Cuevas a document outlining the budget breakdown for all six student centers for the 2023-2024 fiscal year.

This was the first time any SSC employee, student or staff, had seen the document.

During his conversation with Allison and Cuevas, Gorga allegedly attributed the center’s over-expenditure to budgetary misspending on the part of Dean Vazquez. This prompted Higdon’s resignation as faculty tutoring coordinator and brought greater attention to the turbulence that recently washed over the SSC.

In a recent interview with The Inquirer, Gorga said he now plans to meet with the deans and staff of each student center to discuss the goals and budgetary limitations of the centers.

“For me, what’s really important is that I help those students get through their journey,” Gorga said.

“We want to use that [budget] money as effectively as we can to support students as they move through their college career utilizing those centers. So I will work individually and as a group with all of our deans who oversee the centers to make sure that we’re doing that.”

This article was updated on April 1 to reflect newly reported information.